October 29, 2013 — In his youth, Tom Coe struggled tremendously in school with reading, writing and mathematics.

However, his talents blossomed in the shop classes taught in his elementary, middle and high schools, such as metal, wood and electricity classes – those often not found in public schools today.

Coe found great success capitalizing on his skill in building, innovation, equipment and machinery through a career that started with IBM. He now owns 640 acres of industrial-zoned land just north of Valley Springs and he wants to give back to his community.

His dream sits on that land. He envisions a grand vocational school that would train students in all sorts of trades. The first building blocks of this dream are being laid as Coe partners with Steve Christianson, founder of the Water School.

This school prepares students to test for state certifications, allowing them to enter the water utility industry.

With Christianson, Coe hopes to develop a nonprofit water technology learning center on his property, in partnership with school and area utility districts.

Eventually, Coe would like to begin educating students at the high school level.

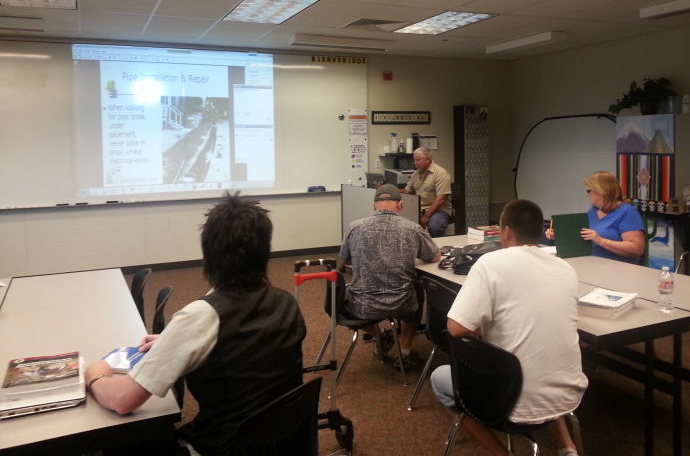

Water School classes offered to Calaveras County residents began in June. Taught by Christianson, a certified water utility plant operator, the classes are offered online, at Jenny Lind Elementary in Valley Springs as well as Minarets High School in O’Neals just north of Fresno.

Classes are held in-person once a week on Friday or Saturday for two to three hours as well as recorded and then broadcasted online for students who missed the class, or take the class online.

Christianson said there are typically 25 students enrolled in the 13-month course. They each take four classes based on the water industry curriculum at California State University, Sacramento, that enrolls students remotely and sends them a book along with a set of questions and test sheets to complete on their own time. The Water School builds upon this in a more engaging and hands-on manner.

“There was no sense in us reinventing the curriculum they already have,” Christianson said. “But with that said, it’s very dry and boring and unless someone is in the industry, it’s very hard to imagine looking at graphics. We bring real-life experience in a multitude of ways.”

There are five levels of mastery when it comes to the water industry – in treatment and distribution – and The Water School prepares students for levels 1 and 2 in the realm of drinking water. In six months, the school hopes to incorporate classes on wastewater treatment.

The school’s courses are structured around the four state tests administered during the year by the California Department of Health Services – that will certify students for levels 1 and 2 in treatment and distribution. Beforehand, Christianson holds an eight-hour review and cram session in the classroom.

Christianson said The Water School guarantees 100 percent pass rate, allowing students to stay on for up to 24 months to continue learning and reattempting the tests should they fail. He said the failure rate in the state is 50 percent.

After graduation, students can spend one year working in the water utility industry and be qualified for the Level 3 certification tests.

According to Christianson, Level 2 certifications tend to lead to jobs paying $40,000 to $65,000 per year, depending on location. Level 3 warrants $60,000 to $90,000 per year.

The school helps students identify a specific career path within the water industry – one that could go in many different directions – eventually working with them on resumes and cover letters.

Brook Silva signed up for the class with some hesitation about four months ago.

The 35-year-old Sonora resident fell into carpentry as a young boy, always onsite with his father, who owned a lumberyard.

After 15 years as a journeyman carpenter, it became increasingly difficult to support himself especially in light of the tanking economy.

“Every time I built a house, I’m thinking, ‘What am I going to do after this?’” Silva said. “I got hurt at work three years ago. Ever since then, it’s been one hard knock after another. So to find something that you know is genuine – nobody can take a state certificate away from you. Nobody can argue that experience once you have it.”

Silva will take his first state certification test Nov. 16.

“I really hope all the studying pays off,” he said. “It’s been a long time since I’ve studied anything but house plans. I don’t know that I could have done it on my own. The support that Steve and Lorraine give me is astronomical. Steve breeds confidence in people.”

Silva imagines a rewarding career.

“Once you’re a water treatment operator, you come home at the end of the day knowing the whole community is drinking the water you created. … The need for water is never going to go away. … Your personal growth is infinite – where you want to stop, where you’re comfortable. I know the higher your certificate is, the easier it is to walk from one job to another without missing a day of work.

Individuals can sign up for The Water School by attending an information session at either Jenny Lind Elementary or Minerats High School, which they can sign up for online at water-school.com.

Though capable of retiring comfortably, Coe feels committed to bringing vocational educational opportunity to the Calaveras region, filling a void in the number of skilled craftsmen available in the country.

“A lot of young people get prestigious degrees and accumulate tons of debt and the jobs aren’t available to them,” Coe said. “There is a tremendous vacuum and need for craftsmen. We need certified welders, machinist and toolmakers. Our businesses are stymied. Most of the craftsmen are in their retirement ages. … We’re going to have a tremendous lack of skill in this country.”

Coe partially attributes this shortage to an image problem with these types of jobs.

“A lot of people have the idea that factories and factory work are dirty, dangerous type of work,” Coe said. “It really isn’t. Our shops today are modern, clean, high-tech – they require a lot of skills in computers, handling machinery and equipment. A lot of them design ingenuity.”

This American stigma is in contrast to places in Europe and Asia, Coe said, where formal training in various trades often progresses for much longer than in the states and such skill sets are often associated with a great deal of prestige.

Coe also cites the dwindling number of apprenticeships available that train such workers.

He dreams of developing a college campus for vocational training on his property, attracting many medium-sized manufacturers to support apprenticeships.

He imagines that students will work 40 to 50 hours per week and get hands-on training, along with 10 to 12 hours of formal classes in technical skills as well as entrepreneurial business training.

In the last year of this imagined five to seven year program, Coe said students would travel the world to gain insight into world competition and opportunities in the world market.

Upon return, Coe said students would develop their own business plans – whether that be to take over an existing businesses or start their own endeavors that the school would help fund.

In Coe’s mind, partnering with Christianson in training up-and-coming water utility plant operators is a step forward in the right direction.

Featured image: Calaveras Enterprise